The Paris Agreement ratified in 2015 saw most countries in the world (196 Parties to be exact) agree to keep the increase in the global temperature of the planet to below 2°C and strive to limit it to 1.5°C. The date fixed to achieve these goals was 2050. But the reality is that, at the current rate, in just over 20 years’ time it will have risen above the first of these thresholds.

Even so, the scientific community estimates that we have all it takes to halt the problem. If we take drastic measures that transform the energy system and social consumption habits, and we can count on the commitment of all the social actors (governments, private sector and society), we will be in time to slow down this uncontrolled rise in temperature.

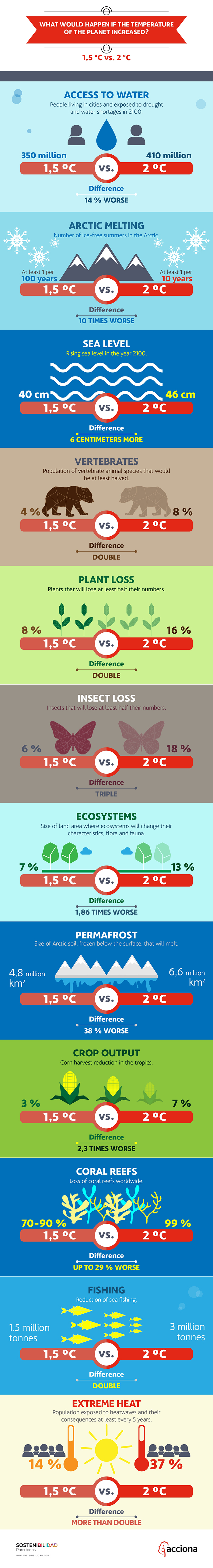

The question is, what happens if nations don’t comply? In the latest IPCC report, almost 100 scientists analyzed what the impact on the planet would be if global warming reached the ceiling of 1.5°C and/or 2°C - and the conclusions are clear: we either get on with it, or we will be left without a planet.

The difference half a degree makes: life

Over the last century, our Earth has already witnessed a vertiginous increase in temperature: 1°C between the pre-industrial era and today. If this progressive rise goes on to reach 2°C, the consequences will, like a cluster bomb, spray in many directions. Never has half a degree mattered so much.

We would experience, for example, an alarming rise in sea level, exposing 69 million people to disasters like flooding in coastal areas. The biodiversity loss we would suffer through an increase of 1.5°C would be catastrophic, but if the rise were to be in the order of 2°C, the problem would be completely irreversible due to the disappearance of plant, animal and insect species, including the death of practically all coral reefs.

Many of our planet’s ecosystems are at risk of radical changes which will kill off their natural biomes. With an increase in the global temperature of the planet of 2°C, some 13% of land, from tundra to forests, would suffer these changes, signifying irrevocable imbalances in their flora and fauna. If the increase is in the order of 1.5°C, the reduction of land area would be down to 4%.

Also, the higher the temperature, the bigger the impact on the Arctic permafrost, 35% to 47% of which would melt with a rise of 2°C, down to 21% if the rise in the global temperature we suffer is 1.5°C.

A variation in the temperature increase of +/-0.5°C would not have the same impact in all the planet’s areas or ecosystems; global warming consequences such as extinction will occur where species no longer have the ability to fight back.

You can’t negotiate with science

The urgency with which the planet is calling for our help to avoid these scenarios requires drastic transformations in the economy and global industry, and a firm commitment by governments, the private sector and society to stop global warming.

To try to keep global warming to 1.5°C in the long term, the world will have to reduce CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030, with respect to 2010, and reach zero net emissions (carbon neutrality) by 2050. To do so, net annual emissions must be reduced to at least half of today’s, i.e. a cut from 52Gt to 25Gt per year. The role of renewable energies will be fundamental in achieving this, and in 2050 they will have to supply 70-85% of all our energy needs.

Radical measures are also needed to replace fossil fuels in transport and improve food production and avoid waste.

Despite this somber panorama, experts remain optimistic: the world does have at its disposal the scientific understanding, technological capacity and financial means to tackle climate change.

Sources: World Resources Institute, Carbon Brief, WWF, The New Climate Economy